© wachiwit / AdobeStock

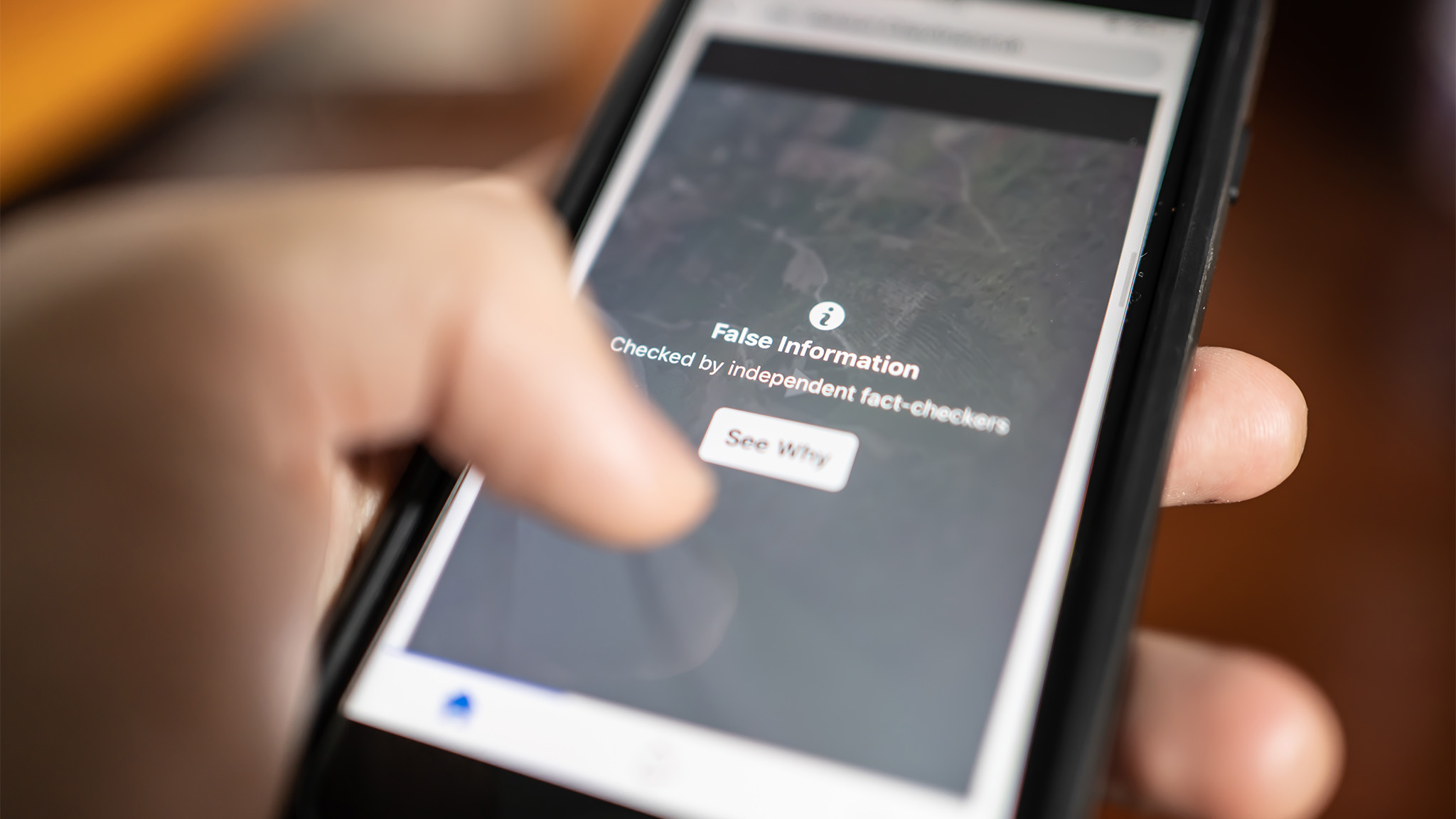

Fake News – What Can We Believe?

Untruths spread quickly – especially online. Professor Cornelius Puschmann investigates why social media channels are particularly well suited for this purpose.

Studies show that untruths rapidly spread via social media channels. These falsehoods are often political news that are being increasingly understood as trustworthy reporting. Why is that the case? And how is it possible to identify fake news?

Usually, it is relatively easy to recognize fake news – incorrect points that are passed on as fact without any truth in them. Fact checks and source investigations can help. However, there are also claims that lie in a grey zone and cannot easily be recognized as being true or false. For example, it is being claimed on the internet that the corona pandemic is being triggered by testing. In short: We have only become aware of the infection from which most people would recover and have no symptoms due to the many tests. “Such statements, which are usually strange interpretations but not definitely fake facts, are a challenge for the fields of science and politics,” says Cornelius Puschmann, a professor of communication and media studies with a focus on digital communication at the University of Bremen.

© Beate C. Koehler

Clarification and Media Competence Are Most Important Tools in Fighting Misinformation

“Misinformation spreads particularly quickly on social media platforms. This is connected to the algorithms that record and influence user behavior,” explains the researcher. The aim of the platforms is usually to keep the users engaged for as long as possible in order to continually feed advertisements to them. That political news, or rather fake news are also available is, however, not something that the platforms desire. The radicalization potential of some user groups can be triggered thanks to the consumption of such information. “It’s a type of ‘side effect’ of social media,” according to Puschmann. And this is where stronger controls are needed. However, as the right to freedom of expression is the greatest asset of a democracy and censorship – even if it is for a “good purpose” - is something that must not exist, clarification and media competence are the most important tools in fighting misinformation.

Controlling Bodies Are Important and Are Being Negotiated

The pressure on government bodies to mark questionable content on internet platforms is growing. But this duty does not solve all problems. Who is allowed to and should mark if something is true or false? Is it not possible that this may then incorrectly include satire? Or radical-democratic political activism? Professor Puschmann explains that the power of the major corporations may even increase in this way and describes a recent situation. Amazon, the largest server hosting service in the world, barred the platform Parler from using its Amazon Web Services (AWS) cloud services due to Parler’s extreme contents. Google Playstore and Apple Store then followed in Amazon’s footsteps and stopped offering the Parler app for download in order to set an example in the fight against misinformation and fake news.

“Those who want to radicalize themselves will do so outside of mainstream platforms. The activity can increasingly be seen on platforms such as Telegram, Parler, or Gab, as there is hardly any systematic controlling of content there.”

“What is questionable is the entitlement to this process, as the companies are opposing the legal obligation to be responsible for their own contents by assessing it – much like it is regulated in press law,” according to the media studies scholar. “Such checks would require a lot of work. Yet the companies want to save their resources,” states Puschmann. “However, what the platform operators are currently doing is removing such content as well as algorithm-based downgrading of “problematic information.” In a targeted search, these measures are noticeable in that certain posts can no longer be found or can only be found with serious difficulty.”

Traffic Light Principle for More Transparency

Individual journalistic initiatives, such as Correctiv, netzpolitik.org, or Abgeordnetenwatch have drawn attention as being further enthusiastic controlling bodies. They check facts, carry out comprehensive research, and make people aware of misinformation campaigns. On a European level, the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO) has been working on stopping fake news campaigns for nearly a decade now. In 2019, individual journalists followed this approach and established the company News Guard in order to be one step ahead of the fake news in terms of algorithms. The browser tool that they developed is based on algorithms and classifies various news channels as being trustworthy and not trustworthy websites by means of a traffic light system. However, the speed with which fake news is spread remains one of the biggest challenges.

Radicalization is Unavoidable but Is Becoming More Visible

The good news is that platform operators need to assess the truth level of their statements in the long term in order to fund themselves through advertisement. This is something that the data giant YouTube ascertained recently as one of its advertising partners pointed out radical right-wing material on its platform. The advertising partner gave YouTube the choice of either removing the content or taking a step back from the advertisement-based financing. Since them, YouTube regularly checks videos that have been flagged as problematic by users. This event has also made it clear that the distribution of misinformation could be channeled in the long term and may only be possible on platforms that can afford to not adhere to content-based regulations.

“Proportion Is Small Overall”

An important message that has resulted from Professor Puschmann’s research is, however, that the internet is in no way a place solely made up of lies and falsehoods. “In comparison to conventional reporting means, there is relatively little misinformation. We’re talking about a small proportion of the overall flow of information on social media,” states Puschmann and summarizes his studies.

What remains crucial is how users implement media. “It also stays true for social media that media does not search for people but rather that every single person is responsible for the media content that they look at or follow.”

More Information:

Professor Cornelius Puschmann investigates the distribution of fake news and conspiracy theories via digital communication channels and contributes to the scientific exchange at the Data Science Center (DSC).