© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

Science That Makes Waves

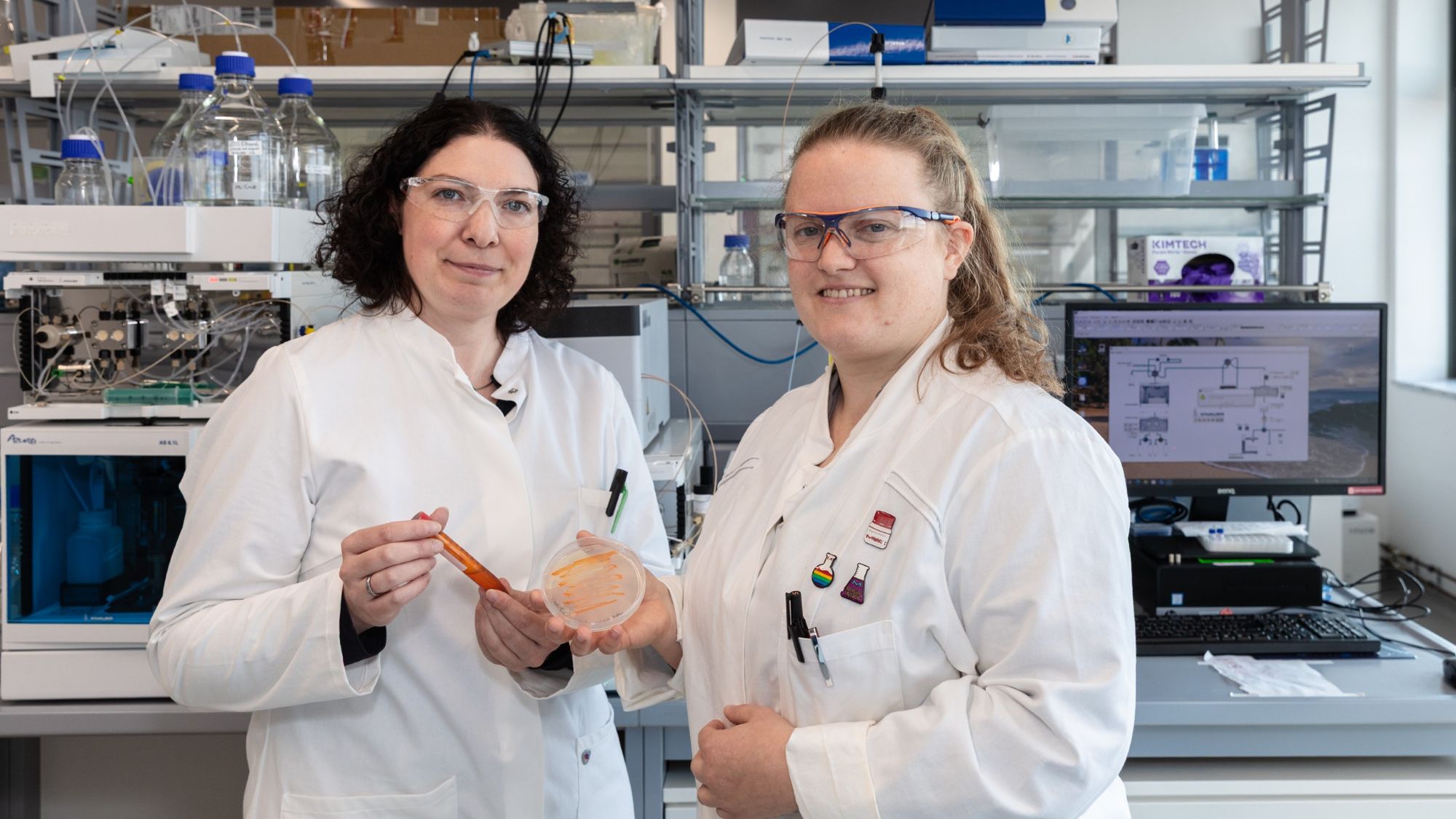

Marine scientists Dr. Christina Roggatz and Dr. Greta Reintjes are both leading their own teams for the first time. A central focus in both of their research is gaining a better understanding of climate change

“The biggest difference in my work now is that I am not just accompanying a research project, but leading my own team,” says Dr. Christina Roggatz. Having completed her doctoral degree and worked as a postdoctoral researcher, she is now managing her own research group, as is Dr. Greta Reintjes. The marine scientists are next-door neighbors in the BIOM teaching and research building, and gave up2date. a glimpse into their work as junior group leaders.

Christina Roggatz became a research group leader with a Freigeist Fellowship from the Volkswagen Foundation; Greta Reintjes within the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft’s (DFG, German Research Foundation) Emmy Noether Programme. These funding programs are known for their exceptional prestige and enable early-career researchers to establish their own teams and pursue an independent research agenda. Both are conducting research on foundational questions of marine biology. Roggatz is investigating how marine organisms such as algae and bacteria communicate with each other, and Reintjes is researching how marine bacteria break down sugar and what effect this has on marine ecosystems.

The researchers’ labs are located right next to each other in the BIOM building. They see this spatial proximity as a great advantage, “We are both leading our first teams of doctoral researchers, technical assistants, and students; and are simultaneously navigating the academic, personnel, and organizational responsibilities that come with it,” says Greta Reintjes. “It is very helpful to be able to talk to each other about our experiences – whether these pertain to research progress, new third-party funding applications, or administrative processes such as ordering equipment or hiring new employees.”

Small Ecosystems, Great Effects

Despite managerial tasks, research remains at the heart of their work. Their research shows the global significance of small-scale processes in the oceans. Christina Roggatz researches how microalgae and bacteria have coexisted and communicated with each other using chemical messenger substances for over a billion years. Over time, they have had to adapt to very different living conditions such as fluctuating ocean temperatures and pH levels. Whether that means that the association between microalgae and bacteria will be resistant to climate change as well is one of the questions Christina Roggatz is seeking to answer.

© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

Greta Reintjes is also researching the interaction between algae and bacteria, albeit from a different perspective. During photosynthesis, algae produce sugar, which is in turn decomposed by bacteria – for example, when they break down dead algae. But how does this degradation process work? Which enzymes are at play? And do different types of bacteria cooperate or compete with each other? These questions are relevant because the CO2 that is produced during the digestion process can then enter the atmosphere. Because of this, Greta Reintjes is particularly interested in how the CO2 emissions can be reduced, which can contribute to mitigating climate change.

Between the Lab and the Desk

Both researchers appreciate the excellent research environment and the great cooperation at the University of Bremen. “We profit greatly from the collaborations within and beyond the BIOM building. Bremen is one of the most important locations for marine research in Germany thanks to institutions such as MARUM, the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research, and Bremerhaven’s Alfred Wegener Institute,” says Greta Reintjes. Both researchers are also involved with the University of Bremen and University of Greifswald’s new CONCENTRATE Collaborative Research Center.

“The scientific collaboration helps us a lot, but we also receive exceptional support from the administration,” Christina Roggatz emphasizes. “Whether in purchasing, human resources, or other areas of administration – our requests are met with open ears. The phrases ‘I don’t want to’ or ‘I don’t have time’ are unheard of here.”

Reintjes and Roggatz hope to carry this attitude into their research groups as well, especially when it comes to providing support to students and doctoral researchers. “It is great to see how students rise to their tasks,” says Christina Roggatz. “Sometimes they are uncertain about how well our topics suit them, but then they get a taste for the research and excitedly plan their own projects.”

© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

This enthusiasm is precisely what unites researchers from both groups. “A person’s field of research, nationality, age, or gender is less important. What matters is our joint commitment to our research,” says Greta Reintjes. Nonetheless, both she and Christina Roggatz have noticed through course evaluations that working together with female researchers makes a difference for female students and can motivate them to pursue a career in academia. Both recall that their own career paths were characterized by only a few female role models in positions of academic leadership. “Which makes it even more meaningful that we are now able to encourage female students to pursue this path,” says Greta Reintjes.

Hope in Times of Climate Change

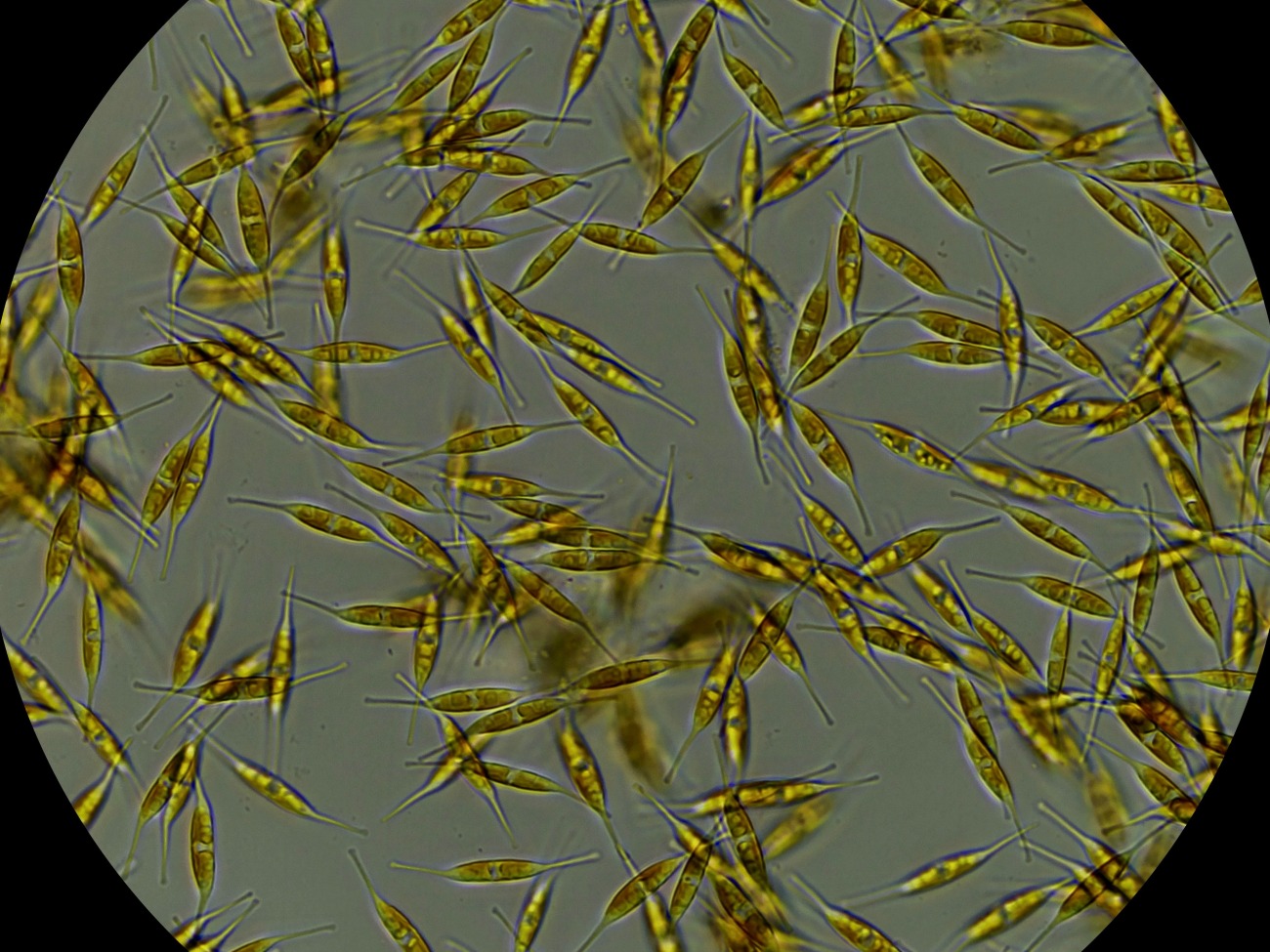

The researchers hope to not just reach other researchers, students, and doctoral researchers, but that their influence will extend beyond the university. As part of their outreach activities, they prepared a course for the Kids’ University, in which children were able to observe algae and bacteria under a microscope. “Many people associate bacteria with dirt and disease and are surprised to discover the important and life-sustaining role these have in the ocean,” Greta Reintjes explains.

© Christina Roggatz

At the same time, the researchers would like to provide children as well as their parents with a new perspective regarding climate change. They often notice that adults approach the topic with exhaustion or resignation, and that there is a prevailing attitude of not being able to change anything. Roggatz and Reintjes want to reach not just the children, but through them their parents and other adults, and to show that science can offer significant contributions to mitigating climate change.

Conducting their own research, leading others, and developing strategies for combating climate change through their own work – all of these are things Greta Reintjes and Christina Roggatz would like to do in the future as well. This is why they aspire to become professors. “We certainly won’t be able to stop climate change by ourselves,” says Christina Roggatz. “But we can contribute our resources to understanding and managing it – through our research, and also by encouraging and empowering others to do their part.”