© Gabriele Senft / Bundesarchiv

Back Then: A Dissident at the University of Bremen

Disgraced in East Germany, welcomed in the Hanseatic City of Bremen: On how Rudolf Bahro came to complete a research stay at the young university in 1980.

Eight years’ imprisonment — that was the sentence handed to Rudolf Bahro by the First Criminal Division of the Supreme Court of the German Democratic Republic on June 30, 1978. What had happened? The court found it proven that the social scientist — a long-time member of the SED — had leaked information to the West German Office for the Protection of the Constitution through his book “Die Alternative — Zur Kritik des real existierenden Sozialismus” (The Alternative — A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Socialism), which was published in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1977. Therefore, the Criminal Court convicted him of “treasonous espionage and disclosure of secrets.”

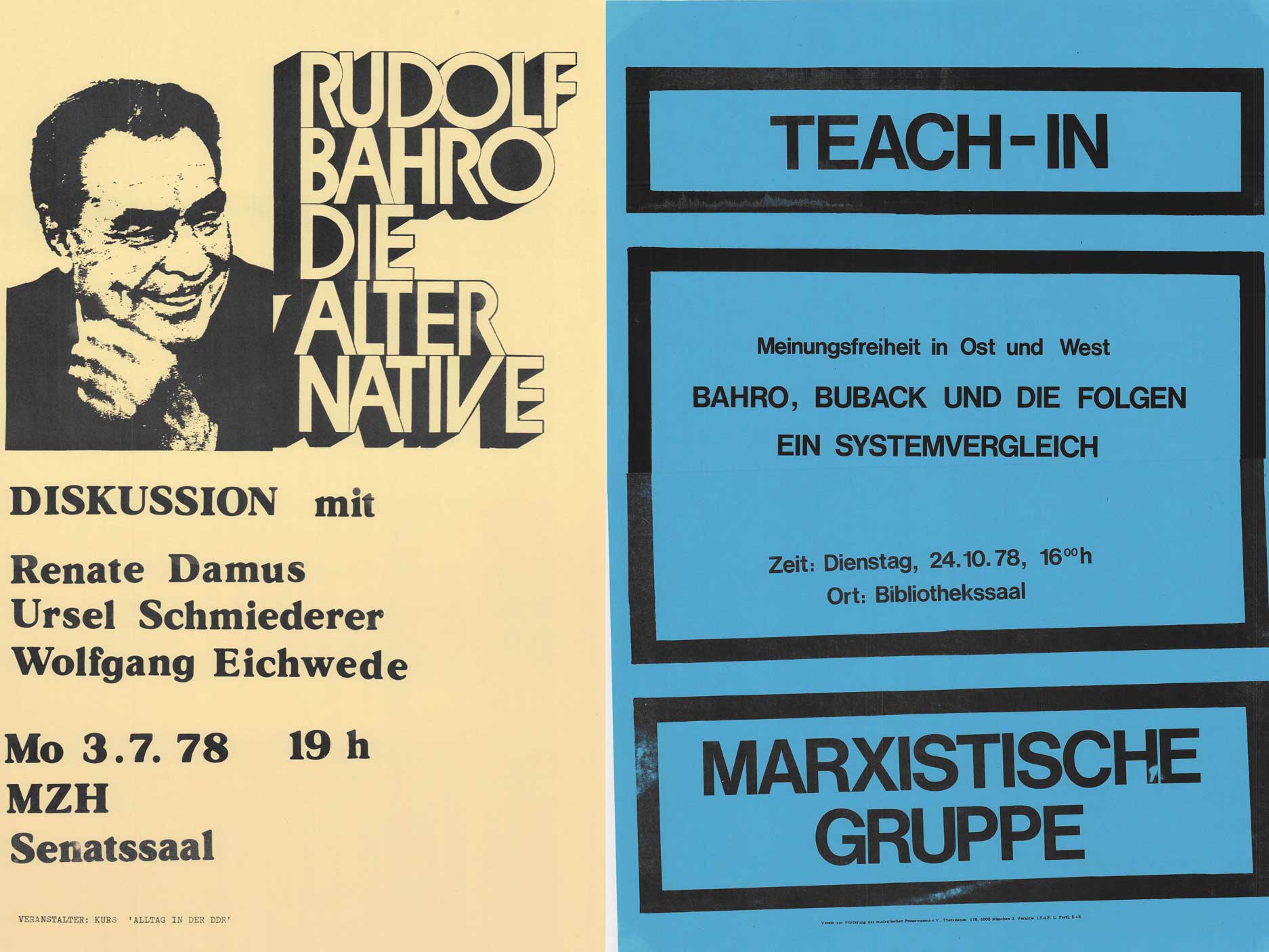

All over Western Europe, Bahro’s conviction and arrest triggered a wave of public outrage and solidarity. This was also the case at the University of Bremen: Teachers and leftwing student groups organized events to inform the public and distributed leaflets demanding his release. In March 1979, the economist Otto Steiger suggested establishing a visiting professorship for Bahro within the economics and social sciences programs (former Faculty 5).

Bahro himself had stated in a letter sent from prison that he would be prepared to go to West Germany if he were released prematurely, since “Marxists of his type” could find a field of work there as well. And, Steiger concluded: “Where could this field of work possibly be more appropriate than at the University of Bremen?”

Visiting Professorship for a Dedicated Communist

A visiting professorship for a dedicated communist — obviously not everyone was immediately excited about this idea. In a letter to the faculty council of Faculty 5 in early July 1979, Steiger expressed his hope that the council would cease in obstructing the visiting professorship “with formal nonsense.”

That same month, the university’s President, Alexander Wittkowsky, addressed the GDR Chairman of the State Council Erich Honecker directly in a letter that was subsequently supported by several intellectuals and politicians — among them sociologist and author Jean Ziegler and former Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme. Wittkowsky asked Honecker to pardon Bahro and took the chance to offer Bahro a two-year research stay at the University of Bremen.

In the end, the massive international pressure worked: On October 11, 1979, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the GDR, Bahro was granted amnesty, released from prison, and allowed to move to the Federal Republic. Anticipating his imminent arrival in Bremen, the Marxist Group (MG) warned Bahro in a welcome note in the October 30, 1979 issue of its Bremen university magazine that his political beliefs would not be met with unanimous approval by both proponents and opponents of communism: “Thus, all prerequisites for a discussion in Bremen are set (…).”

Bahro revealed in a letter of thanks to Wittkowsky that he was at first still reluctant to accept the offer from the University of Bremen. He planned to take up residence in the Frankfurt area. Not long after, however, Bahro did express interest in the Bremen offer, provided the Academic Senate agreed to the request of the President; it did so in December 1979.

The nuclear physicist Jens Scheer — who was banned from working for several years because of his membership in the KPD due to the Anti-Radical Decree (“Radikalenerlass”) — wrote to his “comrade” in a letter in January 1980: “By the way, both of our relations with the University of Bremen are intertwined in a morbidly ironic way, as it has been suggested that your stay here — about which I’d be very happy — be financed from the half of my salary saved by my suspension …”

© Universitätsarchiv

Teaching Positions for Bahro and His Ex-Wife

In March 1980, Bahro moved to Burglesum and began his research activity at the University of Bremen. While his ex-wife Gundula Bahro, who had accompanied him to West Germany, held seminars on children’s and youth literature in the GDR and on contemporary Soviet literature in 1980, Bahro conducted research on the “General Theory of Historic Compromise” from May 1, 1980, to April 30, 1983. In addition to various publications, his research resulted in a class entitled “‘Historical Compromise’ for Western Europe? Fundamental Issues and Problems,” which was held as part of the work studies/politics degree program in the summer semester of 1981.

The “Historic Compromise” was intended to help overcome the divide in the socialist movement and to include non-left democratic forces in order to pave the way for “genuine” socialism and a radically new world economic order. According to Bahro, this was necessary simply because of the “ecological crisis arising from the capitalist mode of production.” If nothing were to change, he believed, “we will, in the course of a few decades, wreck the whole of human civilization, call into question the existence of humankind as a species, and provoke the most serious antagonistic clashes.” Bahro, who in the 1980s increasingly turned to a spiritually influenced communism, made this critique of civilization the focus of his second major work “Avoiding Social and Ecological Disaster — The Politics of World Transformation,” published in Germany in 1987.

Fully Rehabilitated in June 1990

In June 1990, the Supreme Court of the GDR fully rehabilitated Bahro. After German reunification, he rejected proceedings against the jurists who had convicted him in 1978 because he considered it “victor’s justice.” From 1990 to 1996, he directed the Institute for Social Ecology, which he founded himself, at the Humboldt Universität in Berlin. His research focused on ways of living shaped by the industrial society, forms of communitization, and global environmental destruction.

Fortunately, the apocalypse has failed to unfold up to the present day — but the same applies to a fundamental transformation of West European societies and economic forms. Rudolf Bahro passed away in Berlin on December 5, 1997.