© Adobe Stock / photo 5000

Fertile Data

How Sensors and AI Reveal the Content of Manure

Most people associate manure with the pungent smell that wafts across fields and villages. For Professor Karl-Ludwig Krieger and his team at the Institute of Electromagnetic Theory and Microelectronics (ITEM) at the University of Bremen, however, manure is a promising research subject. They are developing sensors that measure nutrient content directly in the field, aiming to make fertilization more efficient and environmentally sustainable.

Liquid manure is a valuable fertilizer rich in nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphate, potassium, and magnesium. At the same time, it can pose risks to groundwater when applied in excessive amounts. “Its composition varies widely depending on the species, feed, and storage conditions,” Krieger explains. “Farmers do send samples to the lab regularly – at least once a year – but the results are only snapshots. They tell us very little about the rest of the manure.”

For a more comprehensive picture, the team uses sensors that measure nutrient levels directly inside the manure tanker, allowing farmers to make precise adjustments to the amount applied. Krieger and his colleagues, Leonard Friedrich and Janek Otto, are pursuing this approach in their iDent and iDentPlus projects, conducted since 2020 in collaboration with industry and research partners.

When Light Meets Manure: Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

The project has two core components: developing suitable sensors and creating the AI-based software needed to analyze the data.

The sensors rely on near-infrared spectroscopy. They emit light at specific wavelengths, which different molecules in the manure absorb to varying degrees. Infrared radiation causes chemical bonds to vibrate; by analyzing how the light is reflected and absorbed, the nutrient content can be inferred.

Developing a practical tool based on near-infrared spectroscopy is challenging. The sensors’ glass must be designed to allow near-infrared light to pass through while withstanding pressure and flow conditions inside agricultural equipment. The sensor must also detect when its measurement window becomes dirty and reliably report this to the system. During the initial project phase, Krieger’s team focused heavily on these practical hurdles.

© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

© Matej Meza / Universität Bremen

Where Sensors Meet AI

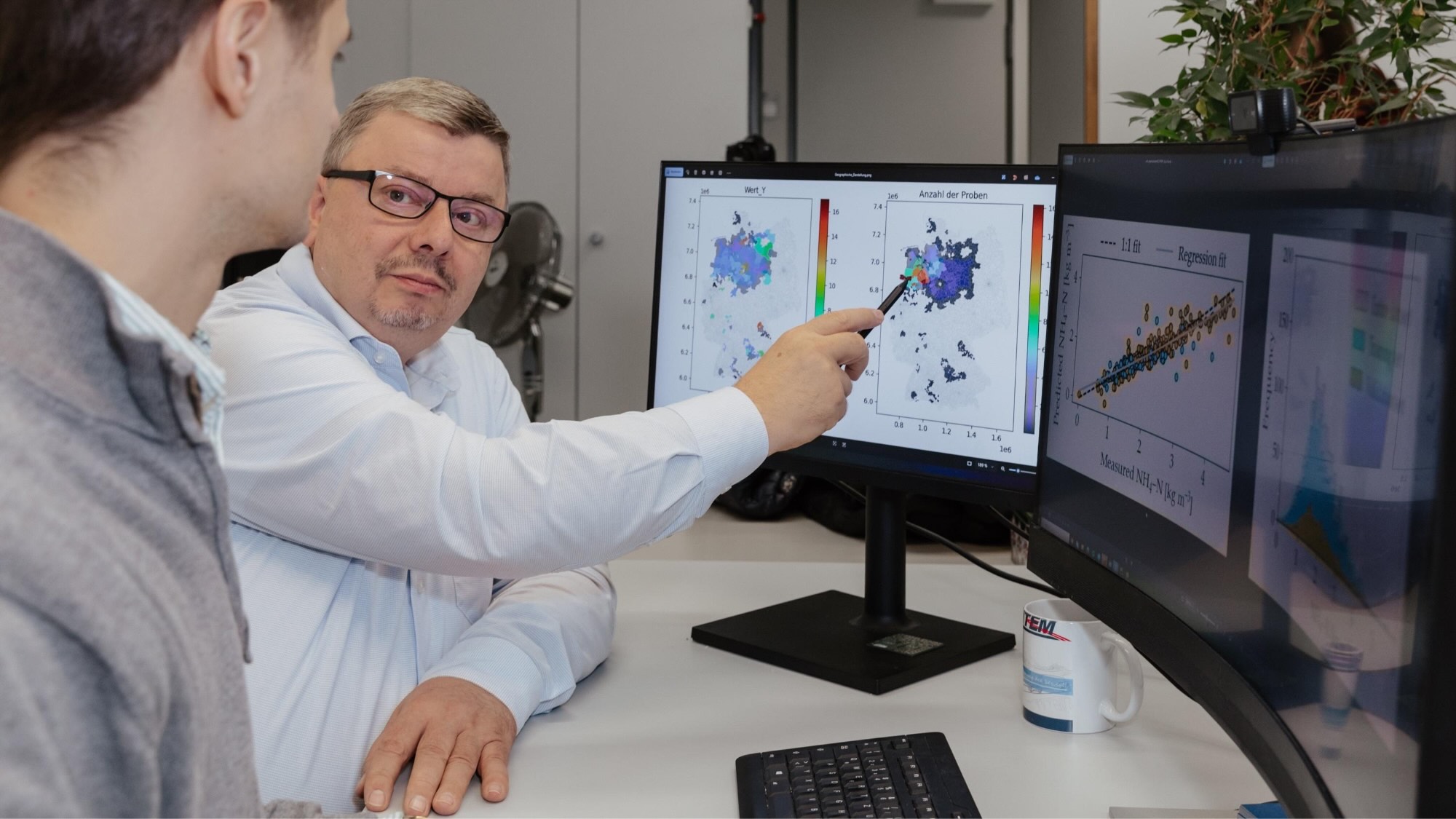

In the project’s second phase, the team has turned primarily to software development, since they could only draw indirect conclusions about the nutrients present in the manure. The challenge lies in interpreting the sensor data: “The sensors don’t measure nutrients the way a thermometer measures temperature,” Krieger notes. “Our job is to discover the relationship between the spectral data and the nutrient levels.” To do this, the researchers align the spectroscopic readings with laboratory analyses and examine how they correlate.

“We can develop the technology, but whether such sensors are approved and actively supported is ultimately a political question.”

So far, they have collected and evaluated more than two thousand samples. With each one, the AI becomes better at recognizing patterns linking absorption spectra to nitrogen, phosphorus, or potassium concentrations. The growing dataset allows the model to make increasingly accurate predictions – eventually enabling it to analyze manure composition from new sensor readings alone, without the need for labor-intensive lab work.

Are on-field nutrient sensors already within reach? The researchers hesitate to give a definitive answer. “We can develop the technology,” says Krieger, “but whether such sensors are approved and actively supported is ultimately a political question.”

Versatile Sensors – From Automated Driving to Manufacturing

Agriculture is just one area where Krieger’s group is applying its expertise. Their broader focus is the development of sensor systems and their integration with intelligent software. In automotive research, for instance, they have designed sensors that measure road surface conditions – an important step toward automated driving.

They are also developing a system for analyzing cooling lubricants, the enriched oils used in mechanical and tool engineering. Improved analysis could extend the usable life of these materials, reduce resource consumption, enhance sustainability, and provide economic benefits.

“That’s what makes our work so versatile,” Krieger reflects. Our approach allows us to operate across many different fields that are socially relevant and meaningfully contribute to sustainability.”